For the past two years, a significant case has been unfolding in Ontario’s Freedom of Information (FOI) system, highlighting the delicate balance between expectations of privacy on our personal devices and the public’s demand for access to government records.

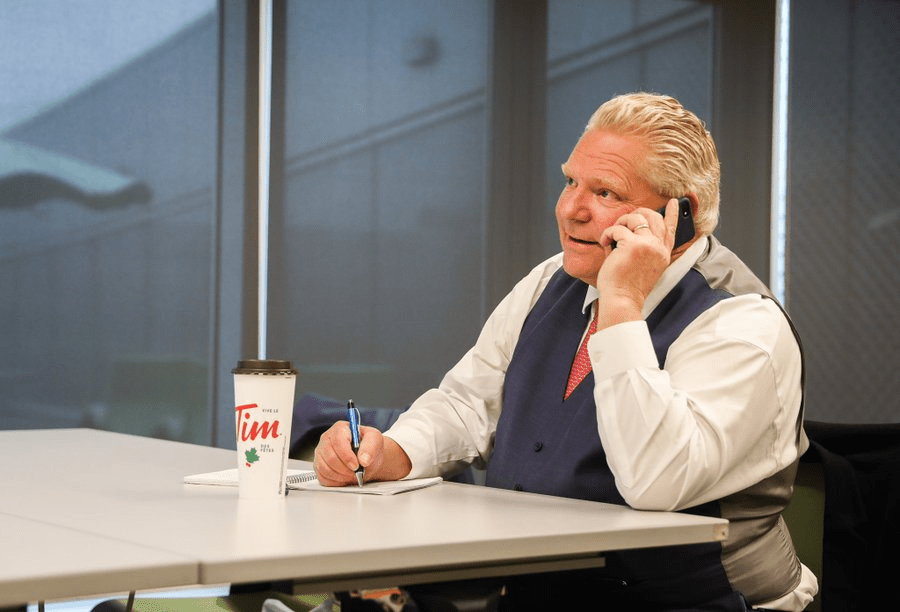

In late 2022, Global News submitted an FOI request seeking access to Premier Doug Ford’s personal cell phone call history records. The request was filed based on allegations that the Premier was using his personal phone for government business.

The request was refused by the Cabinet Office, which asserted that it did not have custody or control over the requested records.

Global News challenged the Cabinet Office’s refusal by appealing to the Information and Privacy Commissioner of Ontario (IPCO), initiating a process that concluded with the issuance of two related decisions: Final Order PO-4576-F and Final Order PO-4577-F, both released by IPCO on November 29, 2024.

In these decisions, IPCO Adjudicator Justine Wai found that entries in the Premier’s call logs which related to government business were in fact under the control of the Cabinet Office. Consequently, she ordered the Cabinet Office to obtain the relevant information from the Premier and to issue an access decision.

These decisions serve to provide significant guidance on when personal records—particularly personal cell phone records—should be considered government records subject to disclosure under Ontario’s FOI framework.

The Final Orders: PO-4576-F and PO-4577-F

Both of the Final Orders adopt the same analytical framework, with the primary distinction being the time periods covered:

- PO-4576-F: Call logs from September 1, 2020, to March 31, 2021.

- PO-4577-F: Call logs from October 3, 2022, to November 6, 2022.

The FOI requests were directed to the Cabinet Office, a government institution subject to FOI under Ontario’s Freedom of Information and Protection of Privacy Act (the “Act”). Although the Orders do not identify the requestor by name, context and media reports confirm that the requestor for one or both of these appeals was Global News. Premier Ford, as the phone’s owner, participated in the appeal as the affected third party. (Given the similarity between the two Final Orders, where any differences arise, this article will focus on the representations of the parties in the first order, PO-4576-F.)

The appeals process was contentious, involving mediation, an inquiry, and procedural disputes.

The Requested Records

The requested records consisted of the Premier’s personal cell phone call logs for the specified periods. The Cabinet Office maintained its position that it had no custody or control over these records, so the adjudicator was not provided with a copy of the call logs during the inquiry.

Procedural Disputes

Prior to issuing the final orders, Adjudicator Wai addressed two procedural issues raised by the Premier:

- Alleged Bias: The Premier argued there was a reasonable apprehension of bias on the part of the adjudicator. This claim was dismissed.

- Disclosure of Representations: The Premier objected to the sharing of his representations with the appellant unless limitations were placed on their use. In response, the adjudicator allowed a redacted version to be shared with the requestor, free of any limitations on its use.

These procedural issues were resolved in Interim Order PO-4532-I and Interim Order PO-4533-I. The inquiry then concluded, leading to adjudication and the issuance of the Final Orders.

Framing the Issue

Adjudicator Wai framed the central issue as whether the call logs were “in the custody” or “under the control” of the Cabinet Office under section 10(1) of the Act, which grants the public a right of access to records in the custody or control of government institutions.

In ascertaining “custody or control,” the adjudicator referenced factors such as the circumstances of a record’s creation, its use, and its relevance to an institution’s mandate:

In deciding whether a record is in the custody or control of an institution, the IPCO has developed a non-exhaustive list of factors to be considered in the particular context of a request and in light of the purposes of the Act. These factors include the circumstances in which a record is created and by whom, its use, and whether the content of a record relates to an institution’s mandate and functions. Also relevant to the issue is whether an institution has physical possession and whether possession of the record is more than “bare possession.”

IPCO Final Order PO-4576-F, para. 12.

Additionally, the two-part test from the Supreme Court of Canada’s decision in Canada (Information Commissioner) v. Canada (Minister of National Defence), 2011 SCC 25 (CanLII), [2011] 2 SCR 306 (“National Defence”) was deemed to apply:

The “National Defence” Test

- Relation to a Departmental Matter: Do the contents of the record relate to a government matter?

- Reasonable Expectation of Access: Could the government institution reasonably expect to obtain the record upon request?

Representations

The Cabinet Office’s Position

The Cabinet Office argued it neither had custody nor control over the call logs because:

- The phone in question was the Premier’s personal device, and was not provided or paid for by the government.

- The logs were not in Cabinet Office’s possession, and it had no authority to access them.

- Applying the “National Defence” test, many calls on the Premier’s personal phone were likely unrelated to departmental matters, and releasing the logs would invade privacy.

- It would be impossible to determine from the call logs what a specific call is about and what exemptions in the Act may apply.

- A “blanket release” of the Premier’s personal cell phone call logs would be “highly invasive” to both the Premier and to the individuals who called the Premier.

The Cabinet Office stated that it would be speculative to assume the logs related to departmental matters. Additionally, it emphasized the privacy concerns of both the Premier and the individuals who communicated with him, including the constituents of his riding.

The Appellant’s (Requestor’s) Position

The appellant contended that the Premier’s call logs were under the control of the Cabinet Office because:

- The Premier’s government-issued phone showed no activity during the relevant period, suggesting government calls must have been made on his personal device.

- Constituents had confirmed that the Premier used his personal phone for public business.

- Allowing officials to use personal devices to evade FOI obligations would undermine transparency.

- If the Premier had made his calls on the appropriate (government-issued) device, the Cabinet Office would have custody and control over the entries relating to these calls.

- The Premier had evaded accountability by using his personal device for government business.

The appellant argued that the Premier’s use of his personal phone for public business created a loophole, undermining the Act’s purpose.

The Premier’s (Affected Party’s) Position

The Premier argued that the request jeopardized privacy and the right of constituents to confidentially communicate with their elected representative. He maintained that:

- The phone logs were private and it was “speculative” whether any related to departmental matters.

- There was no evidence of government business being conducted on his personal phone.

- The phone was not paid for by Cabinet Office or the government.

- The call logs were not in the possession of Cabinet Office.

- The Premier wore “multiple hats” as both an official and as a private citizen, and therefore his personal phone usage should remain private.

IPCO’s Analysis and Findings

After outlining the history and positions of the parties, Adjudicator Wai began her analysis by emphasizing the need for a purposive approach in determining whether records fall within the custody or control of a public body. With this perspective, she articulated the Act‘s dual purposes, highlighting its core balance between privacy and transparency:

It is important to consider the purpose, scope and intent of the legislation when determining whether records are within the custody or control of the public body. In all respects, a purposive approach should be adopted. In determining whether records are in the custody or control of an institution, the relevant factors must be considered contextually in light of the purposes of Act. The purposes of the Act are set out in section 1 as follows:

The purposes of this Act are,

(a) to provide a right of access to information under the control of institutions in accordance with the principles that,

(i) information should be available to the public,

(ii) necessary exemptions from the right of access should be limited and specific, and

(iii) decisions on the disclosure of information should be reviewed independently of government; and

(b) to protect the privacy of individuals with respect to personal information about themselves held by institutions and to provide individuals with a right of access to that information.

IPCO Final Order PO-4576-F, para. 40.

Based on a review of the parties’ representations, and taking a purposive approach with regard to the issue of custody or control, Adjudicator Wai determined that portions of the call logs related to government business were in fact under the control of the Cabinet Office. She reasoned:

- It made sense to conclude that some entries in the logs pertained to departmental matters.

- It was highly unlikely, and unreasonable to believe, that an elected official occupying the Premier’s specific role in government would have conducted no official or government-related calls during the relevant period.

- The relevant test was whether the Cabinet Office had “custody or control”, not both. Showing the Cabinet Office merely had control over the relevant records was sufficient.

- The Cabinet Office could request these records from the Premier.

- The Premier’s decision to exclusively use his personal phone for all matters blurred the lines between personal and professional usage, undermining transparency.

- A determination that the call logs were not in the Cabinet Office’s control would be inconsistent with the purposes of the Act.

Adjudicator Wai stressed the importance of the premier’s government-issued cell phone, which apparently went unused during the relevant period:

The government-issued cell phone was provided to create and log all government-related phone calls and provide a clear separation between the affected party’s personal matters, his constituency matters, and his government or department-related matters. I acknowledge it can be challenging to separate the different roles the affected party plays as an elected official and private citizen. Nonetheless, it is incumbent upon elected officials to use their various devices in their various roles appropriately, to protect the public’s right of access under the Act, and to effectively separate government business from their personal and constituency matters. In this case, it appears the affected party did not make such distinctions between personal and professional matters as he made no calls on his government-issued cell phone. In light of the unique circumstances in this appeal, I find Cabinet Office has control over the call log entries that relate to government or departmental matters.

IPCO Final Order PO-4576-F, para. 52. (Emphasis added.)

The conclusion reached by Adjudicator Wai was that only phone log entries related to government matters were under the control of the Cabinet Office. Personal and constituency-related entries were excluded. Further, although the government-related calls were deemed responsive and subject to disclosure to Cabinet Office, Adjudicator Wai emphasized that such records might still be shielded from disclosure to the requestor by exemptions or exclusions under the Act.

IPCO’s Order to Cabinet Office

Adjudicator Wai therefore ordered the Cabinet Office to “obtain from [the Premier] any government or departmental-related entries from his personal cell phone’s call logs during the requested periods and to seek his views on their potential disclosure” and “issue an access decision on any responsive records that are provided to it by [the Premier], in accordance with the requirements of the Act, treating the date of this order as the date of the request for administrative purposes and without recourse to a time extension.”

Discussion and Implications

The Final Orders make it clear that personal cell phone records are not automatically exempt from disclosure under an FOI request. These decisions reinforce the principle that the use of personal devices for government business does not shield related records from scrutiny under the Act.

That said, it should be emphasized that the records in question were call logs, not more sensitive types of personal data such as text messages, emails, voicemails, photographs, or other files typically stored on a personal phone.

Further, the Orders concluded that only call logs relating to departmental matters are within Cabinet Office’s custody or control. This does raise practical and procedural questions about implementation: How will the relevant “government” logs be separated from those related to personal or constituency matters? Will the Premier alone be responsible for reviewing and redacting his call logs, or will there be oversight by Cabinet Office? If the Premier’s redaction decisions are disputed, is there any avenue for appeal or further review?

Additionally, the Orders stopped short of mandating disclosure of the call logs to the requestor. Instead, the Cabinet Office has been ordered to review the logs, provide the Premier with an opportunity to submit representations as an affected third party, and only then, make an access decision regarding which records should be disclosed to the requestor. While the Adjudicator emphasized that this access decision must be made without recourse to time extensions, delays may still occur due to the involvement of affected parties and further appeals.

Perhaps the Final Orders can be seen as a wake-up call for public officials who conduct government business on personal devices. The use of private devices to avoid transparency runs counter to the Act’s purpose and undermines public trust. Officials must ensure clear boundaries between personal, constituency, and government communications to uphold accountability.

Yet the Orders stop well short of more intrusive measures, such as requiring the phone itself be turned over to IPCO or the Cabinet Office. Instead, the Premier appears to be afforded the opportunity to provide partially redacted call logs for internal review. This approach may reflect an attempt to respect privacy while ensuring some transparency.

The decision also rests on specific and somewhat unique facts. The Premier’s government-issued phone was apparently unused during the relevant period, whereas his personal phone was widely understood to be used for various types of communication. Public statements by the Premier about his constant phone use likely reinforced the Adjudicator’s confidence in her findings. The Premier was known to give out his personal cell phone number and made “frequent references to working 24/7 for the people of Ontario and being always on his phone making calls.” IPCO may be more cautious about ordering the disclosure of records from a personal device in situations where the evidence is less clean-cut.

The Final Orders are likely to serve as influential guidance in future determinations of whether institutions have “custody or control” over records stored on personal devices. They affirm that records related to government business, even if stored on personal devices, remain subject to FOI obligations.

Appeal to Divisional Court

The government has filed a request for judicial review of IPCO’s decisions in this matter. The Final Orders have been stayed pending the Divisional Court review.

Conclusion

IPCO’s Final Orders highlight that personal cell phone records are not automatically exempt from FOI requests, keeping in mind that the cases involved relatively low-sensitivity records (call logs) and strong indications that government business was being conducted on the relevant personal device.

Several practical questions remain:

- If partial disclosure of cell phone records by government officials to their institutions will be the rule, how will departmental matters be distinguished from personal or constituency matters?

- Will government officials be permitted to self-select records for disclosure to their institution, or will there be oversight?

- What are reasonable expectations for the timely disclosure of government records stored on personal devices when procedural disputes and appeals can potentially add years of delay?

This prolonged dispute underscores the importance of public officials maintaining a clear separation between personal and professional communications. The government’s pending judicial review may result in an important court precedent covering the access of government records stored on personal devices. In the meantime, the Final Orders provide valuable guidance when balancing the need for transparency in government with individuals’ expectations of privacy on their personal devices.

The FOI Assist Software

The FOI Assist software was designed by a lawyer with a deep understanding of Ontario’s Freedom of Information system, which means you can trust its guidance and results. FOI Assist streamlines FOI compliance with guided workflows, built-in templates, and advanced reporting features to help provincial and municipal government institutions navigate their responsibilities with ease.

You can start using the FOI Assist software to manage your requests after a brief setup and orientation session conducted by videoconference. Your annual subscription covers everything: setup, live training and support, secure storage, and regular software updates. Our transparent, all-inclusive pricing ensures no hidden costs or unexpected budget variances.

To learn how the FOI Assist software can help you, contact us or schedule a demonstration today.

Make Freedom of Information EasyTM

Follow the FOI Assist Knowledge Base by entering your email in the box below!

Leave a comment